- Research

- Open access

- Published:

The links between symptom burden, illness perception, psychological resilience, social support, coping modes, and cancer-related worry in Chinese early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery: a cross-sectional study

BMC Psychology volume 12, Article number: 463 (2024)

Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to investigate the links between the clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors and cancer-related worry in patients with early-stage lung cancer after surgery.

Methods

The study utilized a descriptive cross-sectional design. Questionnaires, including assessments of cancer-related worry, symptom burden, illness perception, psychological resilience, coping modes, social support and participant characteristics, were distributed to 302 individuals in early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery. The data collection period spanned from January and October 2023. Analytical procedures encompassed descriptive statistics, independent Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, Kruskal-Wallis- H- test, Spearman correlation analysis, and hierarchical multiple regression.

Results

After surgery, 89.07% had cancer-related worries, with a median (interquartile range, IQR) CRW score of 380.00 (130.00, 720.00). The most frequently cited concern was the cancer itself (80.46%), while sexual issues were the least worrisome (44.37%). Regression analyses controlling for demographic variables showed that higher levels of cancer-related worry (CRW) were associated with increased symptom burden, illness perceptions, and acceptance-rejection coping modes, whereas they had lower levels of psychological resilience, social support and confrontation coping modes, and were more willing to obtain information about the disease from the Internet or applications. Among these factors, the greatest explanatory power in the regression was observed for symptom burden, illness perceptions, social support, and sources of illness information (from the Internet or applications), which collectively explained 52.00% of the variance.

Conclusions

Healthcare providers should be aware that worry is a common issue for early stage lung cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. During post-operative recovery, physicians should identify patient concerns and address unmet needs to improve patients’ emotional state and quality of life through psychological support and disease education.

Introduction

Lung cancer is a common malignant neoplasm that often causes considerable psychological distress to patients and their families [1]. Due to the increasing public awareness of health screening in recent years and the use and promotion of low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening for early screening and detection of lung cancer, the incidence of early-stage lung cancer has been increasing [2]. According to the clinical diagnostic criteria for lung cancer, early-stage non-small cell lung cancer refers to a tumor that is confined to the lung and has not metastasized to distant organs or lymph nodes, generally referring to stage I and II [3, 4]. For individuals diagnosed with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer, radical surgical resection offers the most beneficial treatment option for extended survival [5, 6]. It can be said that after diagnosis and active treatment of early-stage lung cancer patients, the recurrence rate 5 years after surgery is low. Although the survival rate after radical resection has improved, a decline in lung function is inevitable. According to studies [7, 8], lung function experienced a steep decline at 1 month after lung resection, partially recovered at 3 months, and stabilized at 6 months after surgery. Patients who have undergone surgery for lung cancer often experience post-treatment symptoms, including pain, dyspnea, and fatigue, which negatively affect their quality of life [9]. A previous study conducted by our team [10] found that post-operative lung cancer patients had various unmet needs during their recovery, including physiological, safety, family and social support, and disease information. The psychological distress experienced by patients, including worry, anxiety, and fear, increases due to unmet needs after cancer treatments [11, 12].

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on Cancer-related worry (CRW) as a form of psychological distress experienced by cancer patients. CRW refers to the uncertainty of cancer patients’ future after cancer diagnosis. It encompasses areas of common concern to cancer patients, such as cancer itself, disability, family, work, economic status, loss of independence, physical pain, psychological pain, medical uncertainty, and death. The purpose of CRW is to reflect the unmet needs or concerns of cancer patients [13,14,15]. Unlike anxiety, worry primarily reflects the patient’s repetitive thoughts about the uncertainty of the future [13]. It is also a cognitive manifestation of the uncertainty of disease prognosis [16].

Currently, measurement scales such as the State Train Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are frequently used to evaluate physical symptoms caused by autonomic nervous activity in patients. However, they do not assess patients’ concerns or anxiety content [17]. Some scholars [13, 17, 18] have developed tools to measure the degree and content of cancer-related worries. The CRW questionnaire is a tool for measuring and evaluating the anxiety status of patients. It can also detect their needs or preferences through convenient means, allowing for the design of personalized care [13]. These questionnaires were primarily utilized to assess the level and nature of worry among cancer patients diagnosed with breast, prostate, skin, and adolescent cancers [19,20,21,22], However, it has not been employed in the post-operative population for early-stage lung cancer.

Theory framework

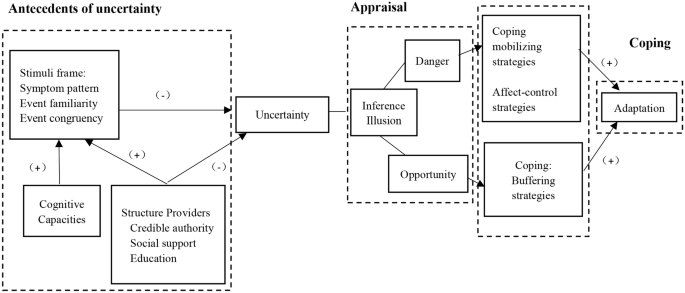

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory [23] defines illness uncertainty as a cognitive state that arises when individuals lack sufficient information to effectively construct or categorize disease-related events. The theory explains how patients interpret the uncertainty of treatment processes and outcomes through a cognitive framework. It consists of three main components (see Fig. 1): (a) antecedents of uncertainty, (b) appraisal of uncertainty, and (c) coping with uncertainty. The antecedents of uncertainty include the stimulus frame (such as symptom burden), cognitive capacity (like disease perception), and structure providers (including social support and sources of disease information). Managing uncertainty requires coping modes such as emotional regulation and proactive problem-solving. Studies [24] have shown that there is a correlation between the way patients manage their emotions and the coping modes they experience when faced with difficulties. Patients with positive emotional coping modes are less likely to worry, while patients with avoidance coping modes are more likely to experience emotional distress. Furthermore, previous research [25] has shown a strong correlation between psychological resilience and cancer-related worries. Psychological resilience reflected an individual’s ability to adapt and cope with stress or adversity, and was an important indicator of a patient’s psychological traits [26]. Furthermore, it had a significant impact on their mental state and quality of life. Specifically, higher levels of cancer worries have been linked to lower levels of psychological resilience.

Based on the theoretical framework and literature research presented, it is hypothesized that factors such as psychological resilience, antecedents of disease uncertainty (symptom burden, disease perception, social support and sources of disease information), and coping modes will correlate with the level of cancer-related worries in postoperative patients with early-stage lung cancer. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the potential correlates of cancer-related worry in early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery. This analysis will aid medical professionals in comprehending the worry state and unmet needs of early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery, and in tailoring rehabilitation programs and psychological interventions accordingly.

Method

Study design

The study was cross-sectional in design. The Stimulating the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was completed (see S1 STROBE Checklist).

Setting and participants

This study included patients who underwent surgical treatment for lung cancer at a general hospital in Shanghai between January and October 2023. The study inclusion criteria were: (1) age over 18 years; (2) clinical diagnosis of early-stage primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Tumor node metastasis classification (TNM) I to II [27, 28], and received video-assisted thoracic surgery; (3) recovery time after surgery was within 1 month. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy or second surgery may be required. (2) If other malignant tumors are present, they may also need to be treated. (3) Patients with severe psychological or mental disorders may not be candidates for this survey. (4) Patients with speech communication difficulties or hearing and visual impairments may require additional accommodations.

Sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9 [29]. Calculate power analysis using F-test and linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 increase as statistical test, and “A priori: Calculate required sample size - given alpha, power, and effect size” as type of power analysis. Cohen’s f2 = 0.15, medium effect size, α = 0.05, power (1-β) = 0.80, number of tested predictors = 8, total number of predictors = 10 as input parameters. The analysis showed that the minimum required sample size was 109 adults. Finally, the required sample size was determined to be over 120 adults with a probability of non-response rate of 10%.

Research team and data collection

The research team consisted of two nursing experts, four nursing researchers (one of whom had extensive experience in nursing psychology research), a group of clinical nurses, and several research assistants. To ensure the scientific quality and rigor of the research, the team was responsible for overseeing the quality of the project design and implementation process. Prior to conducting the formal survey, all research assistants received consistent training and evaluation to ensure consistent interpretation of questionnaire responses.

One month after surgery marks the first stage of the early recovery process for lung cancer patients and is a critical period for psychological adjustment [30]. Understanding a patient’s psychological state is critical to providing excellent medical care. During this period, patients typically need to visit the outpatient clinic for wound suture removal and dressing changes, further emphasizing the importance of postoperative recovery. Therefore, we chose this time frame for our research to gain a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ psychological well-being.

Prior to the start of the study, the hospital management and department head worked with us to provide comprehensive and standardized training to all participating investigators to ensure the reliability and consistency of the study. Research assistants rigorously screened patients based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were designed to ensure a representative sample of lung cancer patients in the early recovery phase.

To obtain informed consent, patients were provided with detailed information and explanations and asked to complete the questionnaire voluntarily. To accommodate the different needs and preferences of patients, we used a combination of electronic and paper questionnaires. The electronic questionnaires were administered via the Questionnaire Star platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), allowing patients to scan a two-dimensional (QR) code to access the survey. For those who preferred paper questionnaires, research assistants provided physical copies and assisted with completion as needed. The questionnaire was designed with consistent instructions to ensure that patients had a full understanding of the questions. Upon completion, each questionnaire was carefully reviewed and checked for accuracy. In addition, to reduce attrition, we obtained patients’ consent to keep their contact information, which allowed us to communicate with them further and collect additional data.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. All participants gave informed consent prior to enrollment.

Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire

We developed a sociodemographic survey based on a literature review and expert consultation. The survey includes patient demographic data such as age, sex, residence, lifestyle, education, marital status, childbearing history, religion, insurance, economic status (annual household income), smoking habits, employment status, sources of disease information, and previous psychological counseling. Clinical case information includes physical comorbidity, clinical tumor stage, and cancer type.

Cancer-related worry

The study measured participants’ cancer-related worry using the Brief Cancer-related Worry Inventory (BCWI), which was originally designed by Hirai et al. [13] to evaluate distinct concerns and anxiety levels among individuals with cancer. For this research, we used the 2019 Chinese edition of the BCWI, as introduced and updated by He et al. [31] (see Supplementary Table 2). The BCWI was comprised of 16 items, which were divided into three domains: (1) future prospects, (2) physical and symptomatic problems, and (3) social and interpersonal problems. Participants were asked to assess their cancer-related worries on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Worry severity was determined by summing the scores for each item. The higher the total score, the more intense the patient’s cancer-related worry. The BCWI provided a concise evaluation of cancer-related worries in cancer patients. With only 16 items, it was able to differentiate them from symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.96.

Symptom burden

The M.D. Anderson Symptom Assessment Scale [32] was a widely used tool for evaluating symptom burden in cancer patients. The Chinese version of MDASI-C was translated and modified by researchers at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. The questionnaire included 13 multidimensional symptom items, such as pain, fatigue, nausea, restless sleep, distress, and shortness of breath, forgetfulness, loss of appetite, lethargy, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, and numbness. Six additional items were used to evaluate the impact of these symptoms on work, mood, walking, relationships, and daily enjoyment. Patients rated the severity of their symptoms over the past 24 h on a scale of 0 (absent) to 10 (most severe), providing a comprehensive assessment of symptom burden across multiple dimensions. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this study was 0.95.

Illness perception

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) was used to measure participants’ illness perception. The scale, developed by Broadbent [33], was later revised by Mei [34] to include a Chinese version. It consisted of eight items divided into cognition, emotion, and comprehension domains as well as one open-ended question (What are the three most important factors in the development of lung cancer, in order of importance? ). The study utilized a 10-point Likert scale to rank items one through eight, with a range of 0–80 points. The ninth item required an open response. A higher total score indicated a greater tendency for individuals to experience negative perceptions and perceive symptoms of illness as more severe. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale of eight scoring items was found to be 0.73.

Psychological resilience

The study measured participants’ psychological resilience using the 10-item Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10), originally developed by Connor and Davidson [35], and later revised by Campbell based on CD-RISC-25. The scale was designed to assess an individual’s level of emotional resilience in a passionate environment. It comprised 10 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always). The total score ranged from 0 to 40 points, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The study utilized the Chinese version of CD-RISC10, which was translated and revised by Ye et al. [36], to measure psychological resilience. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.96.

Coping modes

The study measured participants’ coping modes using the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire (MCMQ), a specialized tool for measuring patient coping modes. The MCMQ was first designed by Feifel in 1987 [37] and was translated and revised into Chinese by Shen S and Jiang Q in 2000 [38]. It consisted of 20 items and three dimensions: confrontation (eight items), avoidance (seven items), and acceptance-resignation (five items). The study utilized a 4-point scoring system to evaluate coping events, with scores ranging from 1 to 4 based on the strength of each event. Eight items (1, 4, 9, 10, 12, 13, 18, and 19) were negatively scored, resulting in a total score range of 20 to 80 points. A higher score indicated a more frequent use of this coping mode. The three dimensions of this scale can be split into three scales for separate use. The reliability coefficients of the Confrontation Coping Mode Scale, Avoidance Coping Mode Scale, and Acceptance-resignation Coping Mode Scale were 0.69, 0.60, and 0.76.

Social Support

The study used the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) developed by Zimet [39] to assess the level of self-understanding and perceived social support in postoperative lung cancer patients. The Chinese version of the PSSS, as adapted by Chou [40], showed satisfactory reliability and validity. The 12-item scale comprised of three dimensions: family, friend, and other support, and was rated using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale’s total score ranged from 12 to 84, with a higher score indicating a greater subjective sense of social support received by individuals. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.94.

Statistical analyses

The questionnaire was validated and double-checked before being input into Excel to ensure accuracy. Statistical analysis and processing of the questionnaire data were conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 26.0 software. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of α = 0.05. The quantitative data were presented using means and standard deviations, while the qualitative data were represented by frequency distributions. The data that conforms to normal distribution was analyzed using independent sample t-test for comparison between two groups and one-way ANOVA analysis for comparison between multiple groups. Non-normal distribution data were analyzed using non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test for comparison between two groups and Kruskal-Wallis -H -Test for comparison between multiple groups. Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was used to study the correlations among CRW, MDASI-C, BIPQ, CD-RISC-10, MCMQ, and PSSS. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to identify the multidimensional factors affecting CRW. All variables significantly correlated with the outcome variable (p < 0.05) were included in the corresponding hierarchical regression analysis. Using Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory as a framework, a four-step model was adopted to study the factors influencing cancer-related concerns. The model includes individual factors such as sociodemographic and disease-related data, as well as psychological resilience, stimulus frame (symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information), and coping modes.

Results

In this study, 307 questionnaires were distributed (227 electronic, 80 paper). Five paper questionnaires were invalid, resulting in 302 valid questionnaires and a recovery rate of 98.37%. The participants were 302 postoperative lung cancer patients, with 36.75% male and 63.25% female, aged 18–83 years (mean age 52.73, SD 13.07). Most patients (90.07%) were married. Additional demographic and clinical information is in Table 1.

89.07% of people had cancer-related worries after surgery and median (interquartile range, IQR) score for CRW was 380.00 (130.00, 720.00) with a range of 0-1600. 86.42% reported worry about future prospects, 84.11% worry about physical and symptomatic problems, 79.80% worry about social and interpersonal problems. Among the 16 worry items of BCWI, the highest frequency of patient worries was “About cancer itself” (80.46%), followed by “About whether cancer might get worse in the future” (79.14%); the lowest frequency concern was “about sexual issues” (44.37%). According to the average score of the items in the three dimensions of CRW, it could be seen that patients had the highest standardized score (standardized score = median score/the total score of the dimension*100%) in future prospects (30.00%), the second standardized score in physical and symptomatic problems (20.00%), and the lowest in social and interpersonal problems (15.00%) as it is shown in Table 2.

On the total score of the CRW scale, patients’ cancer-related worry was significantly correlated with their gender (p = 0.009) and annual family income (p = 0.018; see Table 1). The results suggested that gender and annual family income were related to the level of concern patients had after developing cancer. Additionally, there was a correlation between patients who received information about their disease from the internet or applications and their level of CRW (p = 0.024; see Table 1).

The correlation analysis between various scales revealed a significant correlation (p < 0.05; see Table 3) between CRW and MDASI-C, BIPQ, CD-RISC-10, and two dimensions of MCMQ (excluding avoidance). It was worth noting that avoidance coping modes did not show a correlation with CRW. In addition, according to the summary of the ninth open-ended question on the BIPQ, patients believed that the main causes of lung cancer were genetics, fatigue, stress from work, family or life, negative emotions (anger, worry) and unhealthy lifestyle (diet, work and rest, smoking), environmental factors (poor air quality, secondhand smoke, cooking fumes), and new coronavirus pneumonia (including vaccination, new coronavirus infection), etc. Further stratified linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between the dependent and independent variables (Table 4).

Table 4 presented the results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis for CRW in early-stage lung cancer patients. First, all scales included in the hierarchical regression analysis were tested for collinearity (variance inflation factor, VIF). The average VIF value was slightly above 1, indicating that the results were acceptable [41]. Second, the core research variables were divided into four levels according to the theoretical research, and the variables included in each level were analyzed separately. Model 1 included personal characteristics as independent variables and explained 5% of the variance in CRW. The analysis identified only two variables associated with CRW: being female (compared to male) and having low income (compared to high income). In model 2, psychological resilience was identified as an individual psychological characteristic and placed in the second level, resulting in a 9% increase in explanatory power. Model 3 added the antecedents of uncertainty, including symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and source of disease information, at the third level. This significantly increased the explanatory power of the overall regression model by 53%. The addition of coping modes, specifically confrontation coping mode and acceptance-resignation coping mode, to model 4 only increased the explanatory power of the overall regression model by 1%. The overall model demonstrated a total explanatory power of 68%. In Model 4, factors that significantly correlated with CRW included middle income(β = 2.17), psychological resilience(β=-2.42), symptom burden(β = 12.62), illness perception( β = 9.17), social support( β=-3.27), and source of disease( β = 2.01), as well as confrontation coping mode ( β=-1.98) and acceptance-resignation coping mode( β = 2.77), see Table 4.

Discussion

This study analyzed data from 302 patients to investigate the clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors that correlated with cancer-related worry in patients with early-stage lung cancer after surgery. The study extended our understanding of the specific content and relevant factors of psychological distress in post-operative patients with early-stage lung cancer, a relationship that had not been fully investigated.

The study revealed that Chinese patients with early stage lung cancer were primarily concerned about their future prospects related to the disease itself, while sexual life problems caused by cancer were of least concern. This finding was consistent with previous studies [42], but this study provided more specific information on patients’ cancer-related worries. Lung cancer was widely perceived as a serious illness by the public due to its high cancer-specific mortality rate and low survival rate after diagnosis [43]. Consequently, patients with lung cancer often experience significant psychological distress after diagnosis. Even if the tumor was successfully removed, patients might still face challenges during recovery [44]. According to Reese’s research [45], long-term survivors of lung cancer experienced mild sexual distress. They also noted that sexual distress was significantly associated with physical and emotional symptoms. Although this study found that patients were least concerned about sexual distress, it should be noted that this study was based on the early stages of recovery after cancer surgery. Due to the postoperative repair of their body and emotions, patients were primarily focused on meeting their physiological and safety needs [10]. Further validation and exploration are required as there are limited studies on sexual distress in post-operative patients with early-stage lung cancer.

This study found that gender and annual family income were associated with the CRW of early-stage lung cancer patients. Among them, women and patients from low-income families had higher CRW scores, which was similar to the results of CRW in other cancer studies [14, 46]. The reason might be that women were more conscious about uncomfortable symptoms than men, and women were more concerned about the duration of the disease and subsequent treatment effects than men [47]. Moreover, lower annual family income might cause patients to face more financial pressure in terms of medical expenses and treatment, thereby increasing their concerns about the consequences of the disease [48]. In addition, several other studies have found that education level, smoking status, and tumor stage had an impact on cancer-related worry scores [14, 47], but this study did not show statistical significance.

After controlling for demographic covariate factors, the study found a significant negative relationship between psychological resilience and CRW. In a study conducted by Chen et al. [49], lower levels of psychological resilience were observed in post-operative lung cancer patients, which had a direct impact on their emotional state. In the context of treatment and recovery after lung cancer surgery, medical professionals should prioritize enhancing patients’ psychological resilience. This could be achieved through psychological support and appropriate interventions to improve emotional health and quality of life.

The antecedents in the illness uncertainty theoretical framework, such as symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information, were shown to be significantly associated with patients’ cancer worries in this study. The theory of uncertainty in illness [50] posited that uncertainty was caused by stimulus frames, cognitive abilities, and structural providers. In this study, these antecedents corresponded to symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information, and they correlated with patient worry related to cancer. Patients with a high symptom burden, high illness perception, low social support, and excessive attention to disease information on the Internet were more likely to have high cancer-related concerns. Previous studies [40, 51] have verified the relationship between symptom burden, illness perception, and social support with psychological distress in lung cancer patients. However, there have been few studies on this patient group after surgery for early-stage lung cancer, particularly based on the uncertainty theoretical framework. Additionally, when analyzing the antecedents of structured providers, we included the sources from which patients receive information about their disease, particularly statistics from medical staff and online platforms. Our study found that patients who frequently accessed disease information on the internet had higher cancer-related worry scores. This was consistent with previous qualitative studies [10] which had shown that patients often turn to the internet for disease-related knowledge due to a perceived lack of effective information from medical staff.

This study also explored the association of CRW with coping modes. According to the theoretical framework of uncertainty in illness, coping modes are key for managing uncertainty, as uncertainty influences patients’ coping methods. Previous research [51] has shown that different coping modes can affect patients’ emotional states. Because this study focused primarily on the factors correlated with CRW, we included coping modes as independent variables in the linear regression analysis. The results indicated that CRW was negatively correlated with the coping mode of confrontation and positively correlated with the coping mode of acceptance-resignation. Acceptance-resignation, a negative coping mode, has been shown [52] to be associated with patients’ fear of disease progression and negative attitudes toward the disease, which decreases their confidence in treatment. Poręba-Chabros et al. [53] found that negative coping patterns were significantly associated with depression. When patients adopt an acceptance-resignation coping mode, their compliance behaviors decrease as they succumb to the disease. Conversely, confrontation, a positive coping mode, can enhance patients’ psychosocial adaptability, buffer psychological distress, and improve quality of life [52]. Interestingly, avoidance coping modes did not show a correlation with CRW in the postoperative population of early stage lung cancer, which is inconsistent with previous studies [54]. This lack of correlation may be due to several factors. The focus of our study on the first month after surgery may mean that patients are more focused on immediate physical recovery rather than engaging in avoidance behaviors. The nature of avoidance coping may temporarily alleviate worry without addressing underlying concerns, resulting in no measurable effect on CRW. Sample characteristics, measurement limitations, and individual differences in coping modes may also contribute to bias. In addition, strong psychological resilience, robust support systems, positive surgical outcomes, and increased health education may make avoidance modes less relevant or impactful on CRW in this population. Although the two coping modes were found to be associated with cancer-related worry in our study, hierarchical regression analysis showed that their influence on patients’ worry was small. Future research should explore the mechanisms of cancer-related worry and coping modes based on the theoretical framework of illness uncertainty. Given the association between cancer-related worry and coping modes, psychological intervention for patients should be emphasized in clinical practice. Healthcare professionals should conduct comprehensive psychological assessments and provide effective emotional support and education to help cancer patients develop more effective coping modes and reduce worry caused by uncertainty.

Strengths and limitations

This study presented evidence for CRW and the influencing factors that postoperative patients with early-stage lung cancer face. Based on the results, healthcare providers could identify the specific unmet needs of these patients more precisely and develop effective intervention strategies to improve their emotional state and quality of life. While the existing literature has extensively discussed psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and fear in patients with mid-to-late stage lung cancer, relatively little research has been conducted on the mental health of postoperative patients with early-stage lung cancer, who are an important group of long-term lung cancer survivors [55]. As the number of patients diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer increases, so does concern about their mental health and unmet needs [56, 57].

Nonetheless, this study also has some limitations. First, the single-center cross-sectional design and relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of early-stage lung cancer patients.

Second, while the study adopted a theoretical framework, it primarily conducted basic factor analysis without delving into the interaction mechanisms between the identified factors. This limitation restricts our understanding of how these factors interplay to influence cancer-related worry (CRW) in postoperative patients. In addition, while the CRW variable is largely operationalized in a similar way to the BIPQ and psychological resilience, we found no high correlation between these scales, as indicated by the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). This means that multicollinearity, or the overlap between the variables, is not an issue in our study. However, we recognize that the scales we used may have limitations and might not fully capture the specific experiences of our sample. Therefore, future research should use different methods to measure CRW and related factors to better understand their individual effects on cancer-related worry.

Third, CRW is a dynamic process [20], and this study only focused on the patients’ situation within one month after surgery. This snapshot approach may not reflect the evolving nature of CRW over time. Longitudinal studies are needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how CRW and its influencing factors change throughout the postoperative recovery period.

These limitations suggest that future research should adopt a longitudinal design to analyze and verify the identified factors over an extended period. Additionally, expanding the study to include multiple centers and larger, more diverse sample sizes would enhance the generalizability of the findings. Exploring the interaction mechanisms between factors using advanced analytical methods could provide deeper insights into the complexities of CRW. By addressing these limitations, future research can build on our findings to offer more robust and generalizable evidence on the psychological distress experienced by postoperative early-stage lung cancer.

Implications for practice

The results of the study indicated that early-stage lung cancer patients in China had significant concerns about their future prospects, particularly regarding the disease itself, with less attention paid to the impact of cancer on sexual life. To facilitate postoperative recovery effectively, healthcare providers must promptly identify and address these specific concerns by incorporating routine psychological assessments and developing tailored intervention strategies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and resilience training, to improve patients’ mental health and overall well-being.

Moreover, this study identified psychological resilience, symptom burden, illness perception, social support, sources of disease information (from the Internet or applications), and coping modes of confrontation and acceptance-resignation as key predictors of cancer-related worry in postoperative early-stage lung cancer patients. Managing patients’ postoperative emotional states and enhancing their quality of life requires a deep understanding and proactive intervention by healthcare professionals. Specific strategies include providing psychological assessments, developing individualized care plans, facilitating support groups, and utilizing technology for continuous support.

Conclusions

The study provided insight into cancer-related worry among Chinese patients after surgery for early-stage lung cancer. The results showed that patients were most concerned about their future prospects, particularly the disease itself, while relatively little attention was paid to their sexual distress. The study identified several key factors that correlated with cancer-related worry, including psychological resilience, symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information from the internet, as well as coping modes. These findings emphasized the significance of healthcare providers identifying and addressing the individual needs of patients during post-operative recovery. It is important to improve the emotional state and quality of life of patients through psychological support and disease education. This study provides guidance for post-operative care of patients with early stage lung cancer and suggests avenues for future research. Specifically, further exploration of the mechanisms of these relationships and development of effective interventions are needed.

Data availability

The data that supported the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Meng L, Jiang X, Liang J, Pan Y, Pan F, Liu D. Postoperative psychological stress and expression of stress-related factors HSP70 and IFN-γ in patients with early lung cancer. Minerva Med. 2023;114(1):43–8. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4806.20.06658-6.

Zhu S, Yang C, Chen S, Kang L, Li T, Li J, Li L. Effectiveness of a perioperative support programme to reduce psychological distress for family caregivers of patients with early-stage lung cancer: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(8):e064416. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064416.

Rimner A, Ruffini E, Cilento V, Goren E, Ahmad U, Appel S, Bille A, Boubia S, Brambilla C, Cangir AK, et al. The International Association for the study of Lung Cancer Thymic Epithelial tumors Staging Project: an overview of the Central Database Informing Revision of the Forthcoming (Ninth) Edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18(10):1386–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2023.07.008.

Organization WH. (2023). Lung cancer. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer

Association OSCM, House CMAP. Chinese Medical Association guideline for clinical diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (2023 edition). Chin J Oncol. 2023;45(7):539–74. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20230510-00200.

Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, Senan S, Waller DA, Vansteenkiste J, Escriu C, Peters S. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl4):iv1. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx222.

Gu Z, Wang H, Mao T, Ji C, Xiang Y, Zhu Y, Xu P, Fang W. Pulmonary function changes after different extent of pulmonary resection under video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(4):2331–7. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.03.163.

Chen L, Gu Z, Lin B, Wang W, Xu N, Liu Y, Ji C, Fang W. Pulmonary function changes after thoracoscopic lobectomy versus intentional thoracoscopic segmentectomy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(11):4141–51. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-21-661.

Guo X, Zhu X, Yuan Y. Research Progress on the correlation of Psychological disorders in Lung Cancer patients. Med Philos. 2020;41(2):36–9. https://doi.org/10.12014/j.issn.1002-0772.2020.02.09.

Yang Y, Chen X, Pan X, Tang X, Fan J, Li Y. The unmet needs of patients in the early rehabilitation stage after lung cancer surgery: a qualitative study based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(12):677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08129-z.

Pongthavornkamol K, Lekdamrongkul P, Pinsuntorn P, Molassiotis A. Physical symptoms, unmet needs, and Quality of Life in Thai Cancer survivors after the completion of primary treatment. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(4):363–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_26_19.

Park J, Jung W, Lee G, Kang D, Shim YM, Kim HK, Jeong A, Cho J, Shin DW. Unmet supportive care needs after Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Resection at a Tertiary Hospital in Seoul, South Korea. Healthc (Basel). 2023;11(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142012.

Hirai K, Shiozaki M, Motooka H, Arai H, Koyama A, Inui H, Uchitomi Y. Discrimination between worry and anxiety among cancer patients: development of a brief Cancer-related worry inventory. Psychooncology. 2008;17(12):1172–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1348.

Papaleontiou M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay BL, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Hawley ST, Haymart MR. Worry in thyroid Cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1080–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2019.0163.

Ware ME, Delaney A, Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Armstrong GT, Wilson CL, Mulrooney DA, Wang Z, Lanctot JQ, Krull MR, et al. Cancer-related worry as a predictor of 5-yr physical activity level in Childhood Cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023;55(9):1584–91. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000003195.

Mathews A. Why worry? The cognitive function of anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(6):455–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90132-3.

Gotay CC, Pagano IS. Assessment of survivor concerns (ASC): a newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-15. 5.

Andersen MR, Smith R, Meischke H, Bowen D, Urban N. Breast cancer worry and mammography use by women with and without a family history in a population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):314–20.

Wu SM, Schuler TA, Edwards MC, Yang HC, Brothers BM. Factor analytic and item response theory evaluation of the Penn State worry questionnaire in women with cancer. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(6):1441–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0253-0.

Jackson Levin N, Zhang A, Reyes-Gastelum D, Chen DW, Hamilton AS, Zebrack B, Haymart MR. Change in worry over time among hispanic women with thyroid cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(4):844–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01078-8.

McDonnell GA, Brinkman TM, Wang M, Gibson TM, Heathcote LC, Ehrhardt MJ, Srivastava DK, Robison LL, Hudson MM, Alberts NM. Prevalence and predictors of cancer-related worry and associations with health behaviors in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2021;127(15):2743–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33563.

Jones SM, Ziebell R, Walker R, Nekhlyudov L, Rabin BA, Nutt S, Fujii M, Chubak J. Association of worry about cancer to benefit finding and functioning in long-term cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1417–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3537-z.

Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image J Nurs Sch. 1988;20(4):225–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j1547-50691988tb00082x.

Brand H, Speiser D, Besch L, Roseman J, Kendel F. Making sense of a health threat: illness representations, coping, and psychological distress among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Genes (Basel). 2021;12(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050741.

Gordon R, Fawson S, Moss-Morris R, Armes J, Hirsch CR. An experimental study to identify key psychological mechanisms that promote and predict resilience in the aftermath of treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2022;31(2):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5806.

Harms CA, Cohen L, Pooley JA, Chambers SK, Galvão DA, Newton RU. Quality of life and psychological distress in cancer survivors: the role of psycho-social resources for resilience. Psychooncology. 2019;28(2):271–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4934.

National Health Commission, PRC. (2022). Clinical Practice Guideline for Primary Lung Cancer (2022 Version). Medical Journal of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, 13(4), 549–570.Retrieved from https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.5882.r.20220629.1511.002.html

Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM Stage groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149.

Nelson DB, Mehran RJ, Mena GE, Hofstetter WL, Vaporciyan AA, Antonoff MB, Rice DC. Enhanced recovery after surgery improves postdischarge recovery after pulmonary lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;165(5):1731–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.09.064.

He S, Cui G, Liu W, Tang L, Liu J. Validity and reliability of the brief Cancer-related worry inventory in patients with colorectal cancer after operation. Chin Mental Health J. 2020;34(5):463–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2020.5.013.

Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, Engstrom MC. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7%3C1634::aid-cncr29%3E3.0.co;2-v.

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020.

Mei Y, Li H, Yang Y, Su D, Ma L, Zhang T, Dou W. Reliability and validity of Chinese Version of the brief illness perception questionnaire in patients with breast Cancer. J Nurs 2015(24):11–4https://doi.org/10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2015.24.011

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

Ye Z, Ruan X, Zeng Z, Xie Q, Cheng M, Peng C, Lu Y, Qiu H. Psychometric properties of 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience scale among nursing students. J Nurs. 2016;23(21):9–13. https://doi.org/10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2016.21.009.

Feifel H, Strack S, Nagy VT, DEGREE OF LIFE-THREAT AND DIFFERENTIAL USE OF COPING MODES. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(1):91–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(87)90103-6.

Shen S, Jiang Q. Report on application of Chinese version of MCMQ in 701 patients. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2000;9(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2000.01.008.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCALE OF PERCEIVED SOCIAL SUPPORT. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Chou KL. Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Pers Indiv Differ. 2000;28(2):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00098-7.

Jia JP, He XQ, Jin YJ. Statistics. 7th ed. Beijing: Renmin University of China; 2018.

Zhao F, Liu L, Zhang F, Kong Q. Analysis of fear of cancer recurrence in patients with lung cancer after surgery and its influencing factors. J Nurses Train. 2023;38(17):1619–22. https://doi.org/10.16821/j.cnki.hsjx.2023.17.018.

Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF, Que JY, Liu JJ, Lappin JM, Leung J, Ravindran AV, Chen WQ, Qiao YL, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1487–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x.

Morrison EJ, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Yang P, Patten CA, Ruddy KJ, Clark MM. Emotional problems, Quality of Life, and Symptom Burden in patients with Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(5):497–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2017.02.008.

Reese JB, Shelby RA, Abernethy AP. Sexual concerns in lung cancer patients: an examination of predictors and moderating effects of age and gender. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):161–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-1000-0.

Khoshab N, Vaidya TS, Dusza S, Nehal KS, Lee EH. Factors contributing to cancer worry in the skin cancer population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):626–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.068.

Chen X, He X. Current status of postoperative psychological distress in patients with lung cancer and its influencing factors. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2021;24:3318–22.

Rogers Z, Elliott F, Kasparian NA, Bishop DT, Barrett JH, Newton-Bishop J. Psychosocial, clinical and demographic features related to worry in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016;26(5):497–504. https://doi.org/10.1097/cmr.0000000000000266.

Chen S, Mei R, Tan C, Li X, Zhong C, Ye M. Psychological resilience and related influencing factors in postoperative non-small cell lung cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11):1815–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5485.

Mishel MH, Braden CJ. Finding meaning: antecedents of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1988;37(2):98–103.

Tian X, Jin Y, Chen H, Tang L, Jiménez-Herrera MF. Relationships among Social Support, coping style, perceived stress, and psychological distress in Chinese Lung Cancer patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2021;8(2):172–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_59_20.

Prikken S, Luyckx K, Raymaekers K, Raemen L, Verschueren M, Lemiere J, Vercruysse T, Uyttebroeck A. Identity formation in adolescent and emerging adult cancer survivors: a differentiated perspective and associations with psychosocial functioning. Psychol Health. 2023;38(1):55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1955116.

Poręba-Chabros A, Kolańska-Stronka M, Mamcarz P, Mamcarz I. Cognitive appraisal of the disease and stress level in lung cancer patients. The mediating role of coping styles. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(6):4797–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06880-3.

Park CL, Cho D, Blank TO, Wortmann JH. Cognitive and emotional aspects of fear of recurrence: predictors and relations with adjustment in young to middle-aged cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1630–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3195.

Jovanoski N, Bowes K, Brown A, Belleli R, Di Maio D, Chadda S, Abogunrin S. Survival and quality-of-life outcomes in early-stage NSCLC patients: a literature review of real-world evidence. Lung Cancer Manag. 2023;12(3). https://doi.org/10.2217/lmt-2023-0003.

Jonas DE, Reuland DS, Reddy SM, Nagle M, Clark SD, Weber RP, Enyioha C, Malo TL, Brenner AT, Armstrong C, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer with Low-Dose Computed Tomography: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(10):971–87. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.0377.

Ho J, McWilliams A, Emery J, Saunders C, Reid C, Robinson S, Brims F. Integrated care for resected early stage lung cancer: innovations and exploring patient needs. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2017;4(1):e000175. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000175.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nurses (Especially Gu Jingzhi and Liu Jing) and doctors at Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital for facilitating this study and all the patients who kindly participated in the survey.

Funding

Scientific clinical research project of Tongji University, JS2210319; Key disciplines of Shanghai’s Three-Year Action Plan to Strengthen Public Health System Construction (2023–2025), GWVI-11.1-28; The National Key Research and Development Plan Project of China, 2022YFC3600903.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. and Y. L designed the study. Y.Y., Y.Z., C.S and X.P. ran the study and collected the data. Y.Y., X.Q., X.T. and C.S. analyzed the data; Y.Y., and X. Q. interpreted the results and drafted the paper. Y.Y. wrote the main manuscript text and X.Q. prepared Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. Y.Y., X.T. and Y.L revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (Q23–396). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent for publication Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Qian, X., Tang, X. et al. The links between symptom burden, illness perception, psychological resilience, social support, coping modes, and cancer-related worry in Chinese early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol 12, 463 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01946-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01946-9